A patient presents to you in ER after a traumatic brain injury, showing lucid interval. What will be the most likely diagnosis?

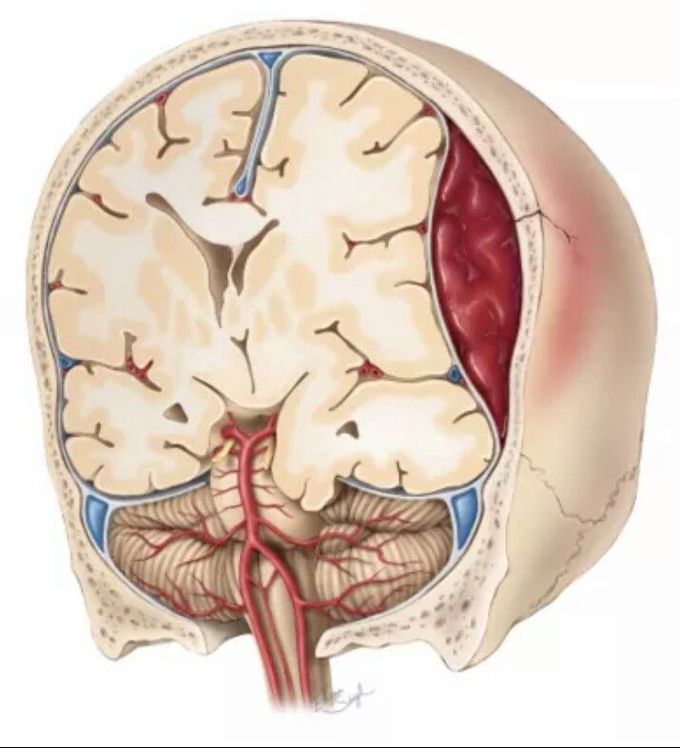

EPIDURAL HEMATOMA It is the accumulation of blood between the skull and the dura. It usually results from arterial disruption, especially of the middle meningeal artery. The dura is adherent to bone, and some pressure is required to dissect between the two. Findings on head CT: The blood clot is bright, biconvex in shape (lentiform), and has a well-defined border that usually respects cranial suture lines. An EDH is typically found over the convexities but may rarely occur in the posterior fossa as well. ✔ Classic, three-stage clinical presentation (seen in 20% of cases): The patient is initially unconscious from the concussive aspect of the head trauma. The patient then awakens and has a “lucid interval,” while the hematoma subclinically expands. As the volume of the hematoma grows, the decompensated region of the pressurevolume curve is reached, ICP increases, and the patient rapidly becomes lethargic and herniates. Uncal herniation from an EDH classically causes ipsilateral third nerve palsy and contralateral hemiparesis. It can also be caused by dural venous sinus tears that rapidly expand and are typically associated with a high degree of morbidity when treated surgically. Open craniectomy for evacuation of the congealed clot and hemostasis generally is indicated for EDH. It can also be caused from bony venous bleeding that is self-limited and may not require surgical intervention. Patients who meet all of the following criteria may be managed conservatively: clot volume <30 cm3, maximum thickness <1.5 cm, and GCS score >8 Prognosis: better for EDH than subdural hematoma (SDH) after successful evacuation. EDHs are associated with lower-energy trauma with less resultant primary brain injury. Good outcomes may be seen in 85% to 90% of patients, with rapid CT scan and intervention. Source: Schawrt’z Principles of Surgery.