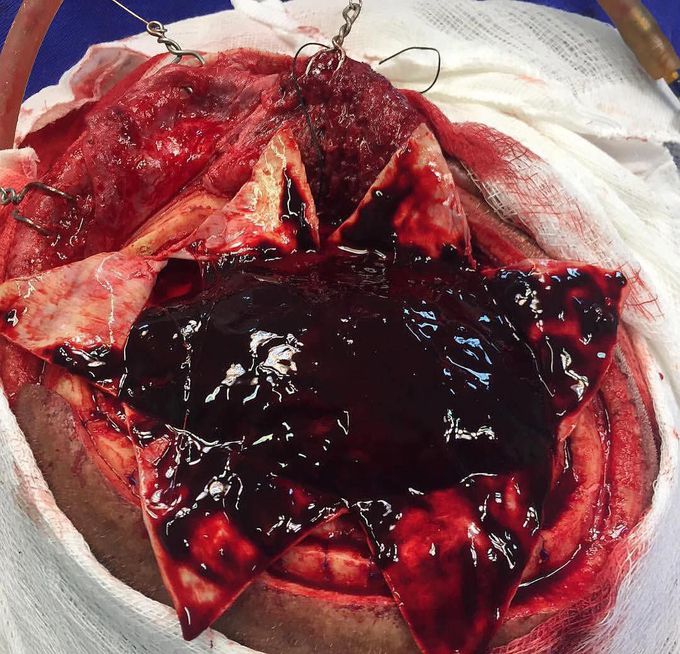

Massive subdural hematoma over the surface of the brain!!

Subdural and epidural hematomas are characterized by bleeding into the spaces surrounding the brain. Subdural hematomas form between the dura and the arachnoid membranes, while epidural hematoma arise in the potential space between the dura and the skull. The usual mechanism that produces an acute subdural hematoma is a high-speed impact to the skull. This causes brain tissue to accelerate or decelerate relative to the fixed dural structures, tearing blood vessels. The torn blood vessel is a vein that connects the cortical surface of the brain to a dural sinus (termed a bridging vein). In elderly persons, the bridging veins may already be stretched because of brain atrophy (shrinkage that occurs with age). Alternatively, a cortical vessel, either a vein or small artery, can be damaged by direct injury or laceration. An acute subdural hematoma due to a ruptured cortical artery may be associated with only minor head injury, possibly without an associated cerebral contusion. Secondary brain injuries are non-traumatic and may include edema, infarction, secondary hemorrhage, and brain herniation. The low-pressure venous bleeding from bridging veins dissects the arachnoid away from the dura, and the blood layers out along the cerebral convexity. Cerebral injury results from direct pressure, increased intracranial pressure, or associated intraparenchymal insults. Patient present with headache, changes in mental status, contralateral hemiparesis, and focal neurologic findings (depends on the lobe being compressed due to a mass effect). Many patients are comatose on admission. These hemorrhage’s can cross suture lines and thus leading to the characteristic crescentic shape seen in noncontrast CT scan.