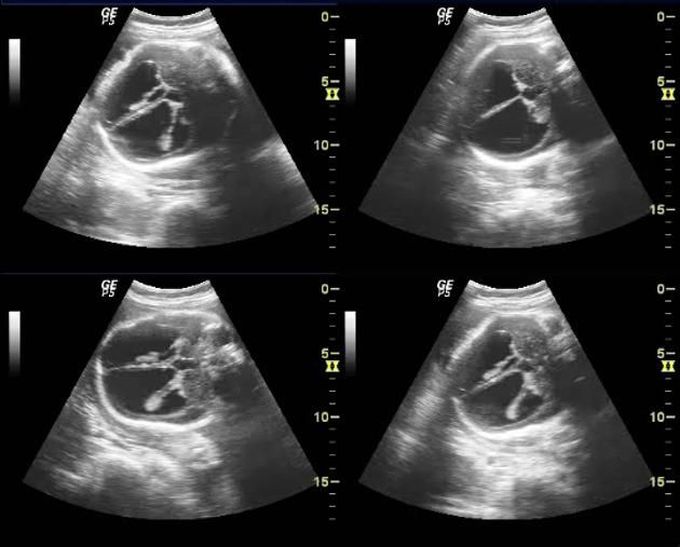

HYDROCEPHALUS

Hydrocephalus Definition Hydrocephalus is a condition in which excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up within the fluid-containing cavities or ventricles of the brain. The term hydrocephalus is derived from the Greek words "hydro" meaning water and "cephalus" meaning the head. Although it translates as "water on the brain," the word actually refers to the buildup of cerebrospinal fluid, a clear organic liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. CSF is in constant circulation within the ventricles of the brain and serves many crucial functions: 1) it acts as a "shock absorber" for the brain and spinal cord; 2) it acts as a vehicle for delivering nutrients to the brain and removing waste from it; and 3) it flows between the cranium and spine to regulate changes in pressure. When CSF builds up around the brain, it can create harmful pressures on the tissues of the brain confined within the skull. The accumulation of CSF occurs due to either an increase in production of the fluid, a decrease in its rate of absorption or from a condition that blocks its normal flow through the ventricular system. Hydrocephalus can occur at any age, but is most common in infants and adults age 60 and older. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), hydrocephalus is believed to affect approximately one to two in every 1,000 children born in the U.S. The majority of these cases are often diagnosed before birth, at the time of delivery or in early childhood. Causes Little is understood about the causes of hydrocephalus. Some cases of hydrocephalus are present at birth, while others develop in childhood or adulthood. Hydrocephalus can be inherited genetically, may be associated with developmental disorders, like spina bifida or encephalocele, or occur as a result of brain tumors, head injuries, hemorrhage or diseases such as meningitis. Based on onset, presence of structural defects or high vs. normal CSF pressures, hydrocephalus can be divided into categories. Acquired Hydrocephalus: This is the type of hydrocephalus that develops at birth or in adulthood and is typically caused by injury or disease. Congenital Hydrocephalus: It is present at birth and may be caused by events that occur during fetal development or as a result of genetic abnormalities. Communicating Hydrocephalus: This type of hydrocephalus occurs when there is no obstruction to the flow of CSF within the ventricular system. The condition arises either due to inadequate absorption or due to an abnormal increase in the quantity of CSF produced. Non-communication (Obstructive) Hydrocephalus: It occurs when the flow of CSF is blocked along one of more of the passages connecting the ventricles, causing enlargement of the pathways upstream of the block and leading to an increase in pressure within the skull. Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: It is a form of communicating hydrocephalus that can occur at any age, but is most common in the elderly. It is characterized by dilated ventricles with normal pressure within the spinal column. Hydrocephalus Ex-vacuo: It primarily affects adults and occurs when a degenerative disease, like Alzheimer’s disease, stroke or trauma, causes damage to the brain that may cause the brain tissue to shrink. Symptoms The symptoms of hydrocephalus tend to vary greatly from person to person and across different age groups. Infants and young children are more susceptible to symptoms from increased intracranial pressure like vomiting and adults can experience loss of function like walking or thinking. Infants Unusually large head size Rapidly increasing head circumference Bulging and tense fontanelle or soft spot Prominent scalp veins Downward deviation of eyes or sunset sign Vomiting Sleepiness Irritability Seizures Children and Adolescents Nausea and vomiting Swelling of the optic disc or papilledema Blurred or double vision Balance and gait abnormalities Slowing or loss of developmental progress Changes in personality Inability to concentrate Seizures Poor appetite Urinary incontinence Adults Headache Nausea and vomiting Difficulty walking or gait disturbances Loss of balance or coordination Lethargy Bladder incontinence Impaired vision Impaired cognitive skills Memory loss Mild dementia Testing and Diagnosis Once a physician suspects hydrocephalus, he/she performs a thorough clinical evaluation, including reviewing and recording a detailed patient history and performing a physical exam to assess the condition. A complete neurological examination, including one of more of the following tests, is usually recommended to confirm the diagnosis and assess for treatment options: Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Lumbar puncture (spinal tap) Intracranial pressure monitoring Isotope cisternography The tests may reveal useful information about the severity of the condition and its likely cause. Once hydrocephalus is suspected, it is important that a neurosurgeon and/or neurologist become part of the medical team for their expertise on interpreting test results and treating the condition. Treatment Hydrocephalus can be treated in a variety of ways. Based on the underlying etiology, the condition may be treated directly by removing the cause of CSF obstruction or indirectly by diverting the excess fluid. Hydrocephalus is most commonly treated indirectly by implanting a device known as a “shunt” to divert the excess CSF away from the brain. The shunt is a flexible tube which, along with a catheter and a valve, is placed under the skin to drain excess CSF from a ventricle inside the brain to another body cavity such as the peritoneal cavity (the area surrounding the abdominal organs). Once inserted, the shunt system usually remains in place for the duration of a patient's life (although additional operations to revise the shunt system are sometimes needed). The shunt system continuously performs its function of diverting the CSF away from the brain, thereby keeping the intracranial pressure within normal limits. In some cases, two procedures are performed, the first to divert the CSF and another at a later stage to remove the cause of obstruction (e.g. a brain tumor). A limited number of patients can be treated with an alternative operation called endoscopic third ventriculostomy. In this procedure, a surgeon utilizes a tiny camera (endoscope) with fiber optics to visualize the ventricles and create a new pathway through which CSF can flow. Follow-up Neurological function will be evaluated after surgery. If any neurological problems persist, rehabilitation may be required to further improvement. However, recovery may be limited by the extent of the damage already caused by the hydrocephalus and by the brain's ability to heal. Because hydrocephalus is an ongoing condition, long-term follow-up by a doctor is required. Follow-up diagnostic tests, including CT scans, MRIs and x-rays, are help determine if the shunt is working properly. A physician should be contacted if any of the following postoperative symptoms are experienced: Redness, tenderness, pain or swelling of the skin along the length of the tube or incision Irritability or drowsiness Nausea, vomiting, headache or double vision Fever Abdominal pain Return of preoperative neurological symptoms Prognosis The prognosis for hydrocephalus depends on the cause, the extent of symptoms and the timeliness of diagnosis and treatment. Some patients show a dramatic improvement with treatment, while others do not. In some instances of normal pressure hydrocephalus, dementia can be reversed by shunt placement. Other symptoms, such as headaches, may disappear almost immediately if the symptoms are related to elevated pressure. In general, the earlier hydrocephalus is diagnosed, the better the chance for successful treatment. The longer the symptoms have been present, the less likely it is that treatment will be successful. Unfortunately, there is no way to accurately predict how successful surgery will be for each individual. Some patients will improve dramatically, while others will reach a plateau or decline after a few months. Shunt malfunction or failure may occur. The valve can become clogged or the pressure in the shunt may not match the needs of the patient, requiring additional surgery. In the event of an infection, antibiotic therapy may be needed and likely temporary removal of the shunt and replacement by a drain until the infection clears. The shunt can then be re-implanted. A shunt malfunction may be indicated by headaches, vision problems, irritability, fatigue, personality change, loss of coordination, difficulty in waking up or staying awake, a return of walking difficulties, mild dementia or incontinence. In infants, the symptoms of shunt malfunction can include the above as well as vomiting, inappropriate head growth and/or sunsetting eyes. When a shunt malfunctions, surgery is often needed to replace the blocked or malfunctioning portion of the shunt system. Fortunately, most complications can be dealt with successfully.

Living with Alzheimer’s disease was one of the hardest experiences of my life. The memory loss, the confusion, and the fear of losing myself weighed on me every single day. I had tried so many treatments and medications, but nothing seemed to stop the disease from progressing.Out of both hope and desperation, I came across NaturePath Herbal Clinic. At first, I was skeptical, but something about their natural approach and the stories I read gave me the courage to try one more time.I began their herbal treatment program, and within a few weeks, I noticed small changes clearer thinking, better focus, and a calmer mind. Over the months, those improvements became more and more obvious. Today, I can truly say my life has changed. My memory has improved, and I feel more present and engaged than I have in years.This isn’t just a testimony it’s a heartfelt recommendation to anyone struggling with Alzheimer’s or other chronic conditions. Don’t give up hope. I’m so grateful I gave NaturePath Herbal Clinic a chance. Visit their website to learn more: www.naturepathherbalclinic.com info@naturepathherbalclinic.com

Dandy Walker Malformation | Diagnosis symptoms and treatment2-Minute Neuroscience: Brain AneurysmsSeizures (Epilepsy) Nursing NCLEX: Tonic-Clonic, Generalized, Focal, SymptomsStroke: Causes, Risk Factors, Treatment, and Prevention | Mass General BrighamNeurofibromatosisBrain Blood SupplyAbsence seizuresSymptoms of absence seizures